According to the 2025 Kubernetes Cost Benchmark Report, average CPU utilization across Kubernetes clusters is approximately 10 percent. For many teams, that raises an obvious question: why is database utilization so low?

The answer is not poor engineering. It is structural.

Modern cloud-native database scaling models are built around peak capacity planning. To protect availability, teams reserve infrastructure far above average demand. The result is persistent database over-provisioning and rising Kubernetes database costs that remain disconnected from actual usage.

As workloads become more burst-driven, especially with AI and event-based systems, the gap between provisioned capacity and real workload continues to widen.

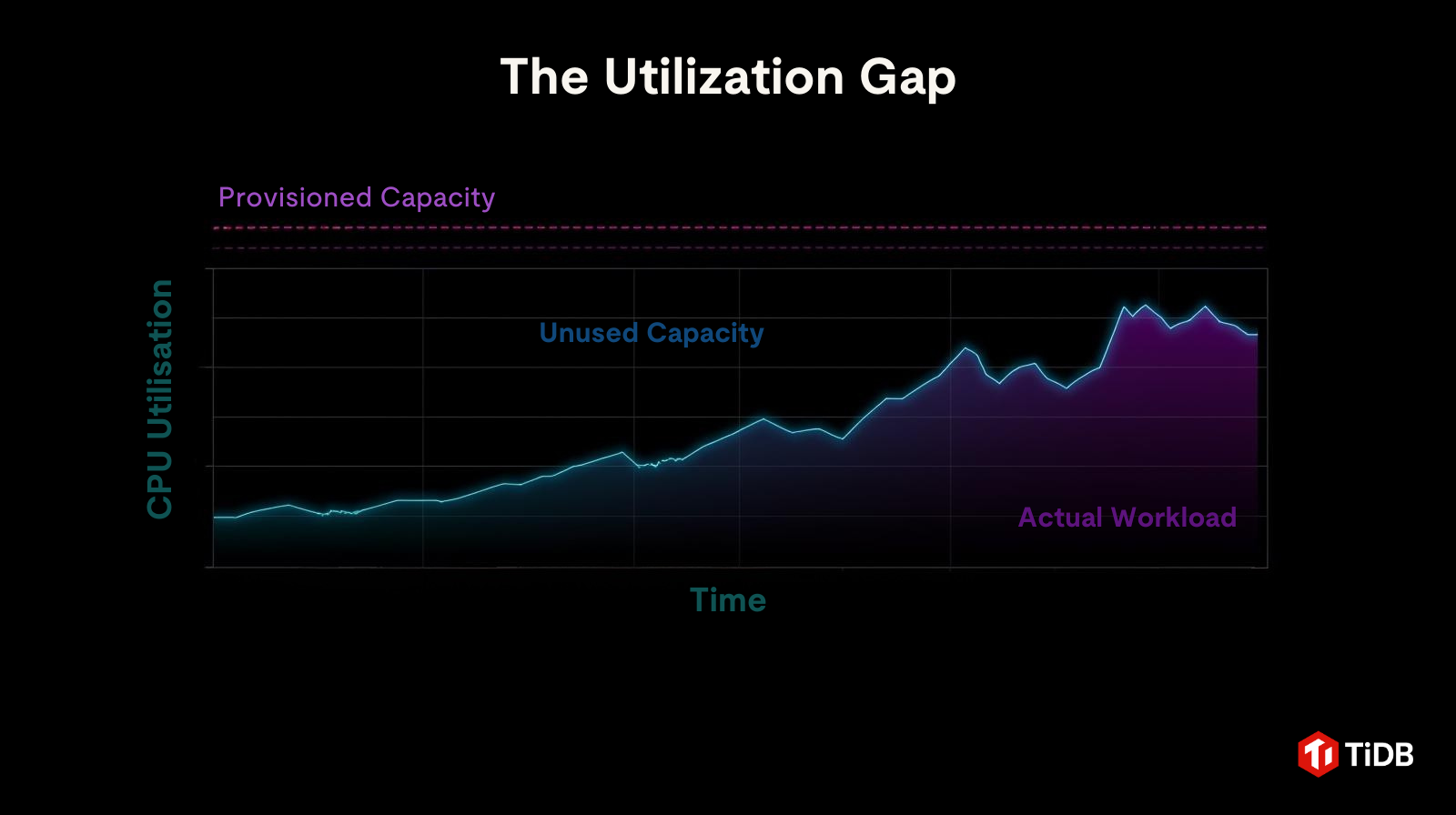

The Utilization Gap

In most production environments, provisioned capacity looks like a flat, elevated line. It handles the worst case by design.

Actual workload behaves very differently. It fluctuates sharply, spikes briefly, and spends most of its time far below the reserved ceiling.

Figure 1: The utilisation gap of database over provisioning

The space between those two lines represents persistent idle spend.

This gap widens during growth events.

The Costs of Sharded MySQL and Conservative Capacity Planning

The cost of this model becomes more visible during planned growth events, such as marketing campaigns or product launches. When teams anticipate significant traffic increases, they are required to provision additional capacity ahead of time. In practice, this typically means:

- Adding new instances.

- Redistributing data across nodes.

- Introducing safety buffers well before demand materializes.

In systems built on sharded MySQL or PostgreSQL, this process can be especially complex. Resharding is not just an infrastructure concern. It often involves application-level coordination, careful sequencing, and meaningful operational risk. Even managed cloud databases reduce operational overhead but still require conservative, advance capacity planning.

In practice, teams end up paying for resources based on projections rather than actual usage. Capacity is secured early, utilization remains low, and the financial cost is incurred regardless of whether demand ultimately meets expectations.

Why Is Database Utilization So Low in Cloud-Native Systems?

Low database utilization in cloud-native systems is often misinterpreted as inefficiency. In reality, it reflects the difficulty of predicting burst traffic in AI pipelines, background jobs, and event-driven workloads.

Consider an AI support agent embedded inside an application.

At 2 PM, it receives a surge of queries. Each request triggers:

- Vector similarity searches

- Context retrieval across multiple datasets

- Concurrent transactional updates

For 15 minutes, the database handles thousands of short-lived, concurrent operations.

Under a capacity-first model, infrastructure must be provisioned to handle that peak. Yet for the remaining 23 hours and 45 minutes of the day, demand runs at a fraction of that level.

The buffer becomes permanent. The burst is temporary.

As variability increases, capacity planning shifts from optimization toward risk avoidance. Larger buffers are reserved for longer periods. The gap between peak and average utilization continues to widen.

When Demand Exceeds Projections

Even careful forecasting cannot eliminate uncertainty.

A campaign expected to generate ten times normal traffic may produce far more. When projections are exceeded, teams typically face two options:

- Add resources under pressure, increasing cost and operational risk.

- Throttle application traffic to protect the database layer.

These outcomes are not the result of poor execution. They reflect a fundamental limitation of systems that require capacity decisions to be made in advance. The experience reinforces conservative behavior. Future plans include larger buffers, earlier provisioning, and an even greater gap between peak and average utilization.

Cloud-Native Database Scaling and the Risk of Scaling Down

Once traffic returns to normal levels, reclaiming efficiency is rarely straightforward.

Why Scaling Down Is Difficult

Shrinking a database cluster is inherently riskier than expanding one.

- Data Integrity Risk: Data must be migrated carefully across nodes to maintain correctness and prevent loss.

- Gradual Decommissioning: Nodes cannot simply be shut off. They must be drained and removed without destabilizing the system.

- Operational Lag: Cleanup efforts often trail the next growth initiative.

Because of this risk, teams tend to move slowly. Over-provisioned capacity often remains in place long after the original spike has passed. By the time cleanup is complete, new growth initiatives are already underway.

These risks create a predictable pattern:

- Capacity grows quickly.

- Utilization drops slowly.

- Cleanup lags behind demand.

Over time, excess capacity becomes normalized and effectively permanent.

The Less Visible Cost: Incentive Misalignment

Beyond infrastructure spend, over-provisioning introduces a subtler challenge.

When systems are oversized, inefficiencies rarely cause immediate pain. Slow queries and suboptimal access patterns still deliver acceptable performance because sufficient headroom exists.

Even when engineers optimize aggressively, infrastructure footprints often remain unchanged. Clusters do not automatically shrink, and costs do not decline.

Over time, this weakens the feedback loop between engineering effort and financial outcome.

How Incentives Diverge Under Capacity Models

| Action | Traditional Database Outcome | TiDB Cloud Outcome |

| Optimize a slow query | Cost remains unchanged due to reserved capacity. | Lower Request Units consumed, directly reducing the bill. |

| Traffic drops 50% | Cost remains fixed for provisioned nodes. | Costs scale down automatically with usage. |

| Eliminate redundant background jobs | Performance improves, but infrastructure spend remains the same. | Reduced workload translates into measurable RU savings. |

When performance gains do not reduce spend, optimization becomes intellectually satisfying but financially invisible.

A Structural Economic Issue

These patterns are not driven by individual decisions or team behavior. They emerge from a cost model where capacity is prepaid, performance gains do not reduce spend, and traffic variability introduces risk rather than flexibility.

As long as databases are priced primarily by reserved capacity, over-provisioning remains the safest option. Caution becomes rational, and experimentation carries an implicit cost.

From Capacity Management to Sustainable Innovation

Over-provisioning often appears to be the safest choice. However, its long-term impact extends far beyond infrastructure spend. It shapes how teams plan, how quickly they experiment, and how comfortable they are with uncertainty. When excess capacity becomes the default, caution quietly replaces curiosity, and innovation slows in subtle but persistent ways.

Modern workloads are becoming more variable, not less. Databases that require teams to predict the future increasingly constrain what those teams can attempt in the present. The real question is no longer how to provision capacity more efficiently, but whether capacity planning should remain the primary control mechanism at all.

Databases should not force organizations to choose between stability and ambition. Over-provisioning is not an operational failure. It is a signal that database economics no longer match modern workloads.

Usage-Based Database Pricing vs Reserved Capacity Models

Usage-based database pricing changes the economic structure of cloud-native infrastructure. Instead of paying for reserved capacity, teams pay for actual work performed by the database. This model directly challenges the cost assumptions behind traditional Kubernetes database costs.

TiDB Cloud approaches this challenge by changing the economic relationship between workload and cost. Compute resources can scale down when workloads decrease, allowing costs to fall during periods of low activity. Idle capacity is no longer a permanent expense.

Importantly, this elasticity is not simply reactive scaling. Waiting for utilization thresholds before adding capacity still introduces delay and risk. TiDB Cloud is designed to absorb variability as a first-class behavior, with pricing and architecture aligned to that assumption rather than layered on top of fixed-capacity models.

In addition, TiDB Cloud meters usage through Request Units, which reflect the actual work performed by the database. Query execution consumes measurable resources, and improvements in efficiency directly reduce consumption. Optimization becomes immediately visible in cost metrics.

Production-Ready at ~$20 Per Day

You don’t need a major architectural overhaul to move away from over-provisioning.

With TiDB Cloud Essential, many small production workloads run at approximately $20 per day.

That price includes:

- 99.99% availability with built-in multi-zone protection

- 30 days of point-in-time recovery, enabled by default

- Usage-based autoscaling up to 100K Request Units

- Encryption in transit and at rest

This is not a limited trial tier. It is a fully managed, production-grade database designed to handle real traffic variability.

Instead of provisioning for worst-case scenarios, you can deploy a real workload and let the cost scale with actual usage. Spend decreases as demand falls. Engineers can further reduce consumption through optimization. Meanwhile, the system scales automatically to handle traffic spikes.

Start with one production workload. Measure the operational impact. Compare the cost profile. Then decide whether fixed-capacity economics still make sense for your environment.

Sign up for TiDB Cloud Essential and run your next production workload without over-provisioning.

Spin up a database with 25 GiB free resources.

TiDB Cloud Dedicated

A fully-managed cloud DBaaS for predictable workloads

TiDB Cloud Starter

A fully-managed cloud DBaaS for auto-scaling workloads