Most companies suffer from a serious problem that limits their growth, and most don’t even know it. By the time they find out, it’s costing them millions in missed opportunities for product progress. It’s an infrastructure bottleneck — the root cause of most major issues with online applications. It causes downstream outages. It slows, and can even halt, product development. I’m talking about the elastic scalability of the data layer.

There’s a reason the databases that sit under most revenue-driving applications are incredibly old. The backbone of an application — the source of truth for all users — is a daunting thing to change. But we live in a time where the choice is between changing or staying complacently knee-deep in mud.

Today, the world looks different. The number of users available to monetize has grown immensely. So has the amount of data needed to keep them happy. Every product decision technology orgs make has a potential impact on growth. That makes scalability an existential concern.

A Hidden Bottleneck to Growth

As a rule of thumb, we call an infrastructure scalable if it can maintain flexibility, performance, reliability, and operability as business demands increase. In a truly scalable system, growth has no impact on operations except for the additional cost of resources like storage and compute.

That’s the ideal. In practice, businesses tend to hit a point where scaling becomes exponentially harder. The problem comes on slowly. Fixing it can take even longer. This is most evident at the data layer. At the heart of the data layer are the application’s sources of truth; its systems of record. These are where application data changes happen first and remain longest. They are typically served by relational, ACID-compliant databases, which are notoriously “sticky.” The very properties of these databases that enforce data integrity have historically made them very resistant to changes in the application.

Changes to the data layer come in many forms, most of which are downstream of the business or the application. One form is growth in the number of users, as the business adds more customers. Others may have to do with the amount of data you ingest, read, and manage per user, as applications add features and the business finds more ways to leverage data it collects. It could be any or all of the above. Whatever the scenario, the growth in users, user data, and frequency of queries pressures the data layer to do something it was historically not built to do: expand. If the database can’t easily scale, innovation gets impeded or rejected. Tech debt increases. Maintenance costs rise.

This problem is a failure of architecture. Monolithic ACID databases are, at their core, designed to be run on a single instance. As pressure increases on them, applications incur higher latency, lower availability, and ultimately failure.

Distributed SQL: A New Architectural Paradigm

So if dynamic scaling is an architectural problem, what does an architectural solution look like?

Distributed SQL is the most modern answer to this question. Inspired by innovators at Google, distributed SQL architectures are specifically designed to handle scenarios where an organization has outgrown its monolithic relational system. It is an ACID-compliant relational database cluster that scales writes, reads, and data stored horizontally.

To illustrate how distributed SQL differs from a traditional SQL RDBMS, I’ll refer to the open source distributed SQL database TiDB.

Inside TiDB: The Architecture of Scaling Throughput

The most obvious bottleneck in a system that enforces strong data integrity like ACID compliance is how you safely distribute (scale) data-modifying transactions. This is impossible in traditional application databases.

However, TiDB — inspired by multiple paradigm-shifting Google papers — does gracefully support horizontal scale of these transactions. Where one ACID-compliant SQL instance controlled write consistency through a single transaction management process, TiDB allows for unlimited transaction managers simultaneously. TiDB automates database sharding behind the scenes, totally transparent to applications. Developers will never need to think about sharding.

Distributed Write Consistency Enabled By “Multi-Raft”

The first problem of scaling transactions is enforcing the write consistency required to ensure durability and availability of all data written. TiDB stores schemas and tables of any size in many small moveable “shards” called “regions” or key ranges, scattered across a cluster of storage nodes. A single node may have hundreds of thousands of these “shards” and a cluster may have many millions. These key ranges are their own raft replication groups (“raft groups”), guaranteeing that every write is replicated to a majority of replicas. Any raft group may accept writes simultaneously. This is referred to as a “multi-raft” or “multi-write” architecture. The number of simultaneous writes against the system scales with the cluster.

This is roughly illustrated below (TiKVs are TiDB storage nodes).

Distributed Transaction Atomicity Enabled By 2-Phase Commit

Write replication consistency is only part of the problem when you distribute important data across many nodes. In relational systems, a single business-driven data change may happen in multiple nodes. The business requires all of the data changes to succeed…or else none succeed. This is called atomicity. TiDB enforces this as well.

To do so, it leverages the Percolator 2-phase commit (2PC) protocol, a sophisticated key locking algorithm, to guarantee all or none of a transaction is stored. This achieves atomicity even in cases where large data-modifying transactions are “fanned out” to many storage nodes. The larger the transaction, the more important this is. And TiDB supports any size transaction.

It’s an eye chart but, for the curious, below is a visualization of the 2PC framework implemented in TiDB.

Transaction Contention Solved By MVCC

When you horizontally distribute a transactional workload, many transactions may occur at the same time. Businesses require that each of these transactions see a consistent view of the data the whole time the transaction is processing. In other words, no data change from transaction T2 that occurred after transaction T1 started will be seen by T1. TiDB achieves this by enforcing Snapshot Isolation.

TiDB accomplishes this with multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) to store multiple versions of recently modified data in order by timestamps, enabling time-based snapshots of the entire cluster and providing snapshot isolation.

This combo of multi-raft, 2PC, and MVCC allows for extremely high throughput of ACID transactions of all kinds that are horizontally and linearly scalable.

Read Performance Enabled By a Compute Layer Designed For Distributed Data

TiDB’s query cost optimizer inherent to the SQL compute layer is distributed-aware. It understands distributed table statistics to optimize plans for how queries will be executed, and it knows locations of key ranges of table data to more optimally execute the cost-optimized query plans. This all keeps query latency low as the cluster scales.

Cost and Complexity of Scaling Optimized By Physical Architecture

TiDB’s architecture is not only distributed but disaggregated. Compute and storage are separated. The separation of compute from storage allows for an important separation of concerns, mainly of state. TiDB compute nodes are agile and can be added and removed with ease. When added, they become ready for serving traffic almost immediately. Together, these properties make TiDB faster and more cost-effective to scale out.

Parallelism in Practice: How Distributed SQL Powers Scalable Operations

The aforementioned properties facilitate horizontal scaling of data workloads that were not previously scalable. But there’s more reason to consider the true scalability of a data layer than simply increasing throughput and storage of critical data. A system may scale to meet the needs of the workload, sure. But, once in place, can it bend to the needs of a changing business? This is an all too overlooked consideration when choosing scaling systems.

As a system writes and stores more data, the entire paradigm of the database changes. It has to account for:

- More data to reorganize when schema changes

- More schemas to change

- More data to backup and restore

- More data to replicate to downstream systems

- More data to move when scaling up, scaling down, or recovering from outages

Databases can get so bogged down by these operations, businesses will actively avoid using them. Obviously, this destroys developer velocity and stifles business growth.

Distributed SQL systems have the opportunity to parallelize these operations so that as the workload scales, the speed of these operations remain largely constant. TiDB takes these opportunities.

Flexibility Served By Fast, Online Schema Changes

Arguably most important, and an often overlooked aspect of scaling — is how often the database’s schema can change, and what it means for the business if that process slows down – or worse, can’t be accomplished at all. Typically, the larger the schemas and tables, the more cumbersome the process becomes, and the less likely it is that orgs will try to make those changes in the first place. In the most extreme cases, the difficulty of modifying a database schema can keep developer orgs from providing certain features at all.

In addition to transactions, TiDB leverages its distributed architecture for schema changes as well. For instance, when adding an index, data must be read and reorganized. TiDB splits the reading into many workers and splits the reorganizing of the data into many other workers, all scattered across the cluster. This means schema changes do not slow down as the business scales. This mechanism also leverages cloud-native technology like external object storage for storing temporary results, making the entire operation less expensive and more stable.

Availability At Scale Supported By Dynamic Fault Tolerance

When a storage node goes down for any reason, the architecture of many mini raft-replicated shards can save the day. Raft leadership is transferred immediately to consistent replicas contained in the remaining live nodes. This enables reads and writes against the keys that were being served by the downed node. As a result, the availability of your application’s most important data is unmatched.

The above illustrates the multi-raft mechanism during a storage node outage and recovery. A node goes down (upper left), taking down the shard leaders that were on that node. The cluster quickly realizes this and re-elects leaders on remaining nodes (upper right). During the time to “realization” of the outage, there is a blip in availability loss on the affected keys, followed by a very quick recovery to normal throughput picked up by the remaining nodes (bottom).

This means the larger the cluster, the less impactful a node outage.

Agility Supported By Efficient Scale-Up/Down

A many-shard architecture also mitigates the classic challenges of scaling out a sharded system and making sure data is still balanced. This architecture makes for easy redistribution to new nodes, balancing the workload as soon after scaling as possible. The larger the cluster, the faster the scale-out. Scale-down operations are similar.

Multi-Tenant Scaling: Simplifying SaaS Growth

In SaaS deployments, scaling up often means scaling up the number of “tenants”: users that are logically walled off from one another for privacy, performance and security purposes. More tenants means more objects like schemas and tables. This in turn means more metadata to manage and more optimizer statistics to collect.

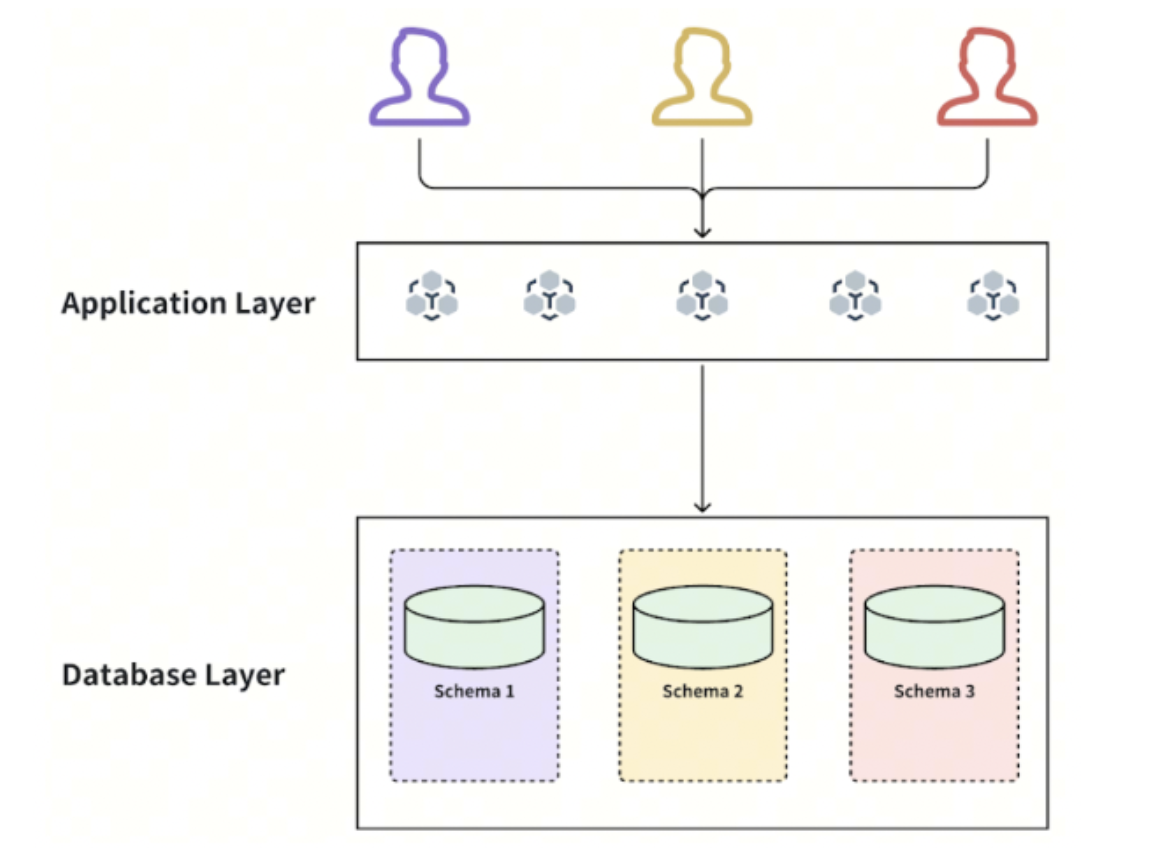

Compared to traditional SQL, distributed SQL architectures can more easily accommodate multi-tenant environments. I’ll illustrate with an example.

How Atlassian Scaled 3 Million Tables with TiDB

Atlassian recently launched its fully managed developer platform, Forge SQL, enabling 3rd party developers to extend or entirely build their own businesses on top of any Atlassian product, like Jira. They give their builder customers an interface to essentially work with the app database directly.

Atlassian uses TiDB as the scalable backend to serve Forge SQL, providing each of Atlassian’s 3rd party developers a shared database system to store their own customers’ data. This raises several traditionally difficult SaaS backend engineering questions.

To provide each Forge customer their private data, each gets their own schema/s. But that means potentially a whole lot of those, and potentially a whole lot of trouble. But TiDB is designed with this challenge in mind, as shown below.

To start, TiDB handles the initialization of these schemas by allowing parallel creation of databases and tables, drastically speeding up object creation at scale.

More importantly, there is the problem of each of these customers wanting to change their schemas without interrupting their own customers’ experiences, and the experiences of every other Atlassian customer’s customers. For this, TiDB provides distributed, in-place and online DDL, allowing operators to migrate schemas for every tenant much faster without interrupting online traffic.

How Atlassian Makes Changes to Its Forge SaaS Platform

If Atlassian needs to roll out changes to all Forge customers at once, TiDB offers parallel schema migrations—also online. Instead of executing a schema change on one object, temporarily stopping traffic to that object, waiting for it to finish, resuming traffic against it and then repeating that possibly millions more times (in SaaS cases), TiDB executes the changes in parallel.

Bear in mind that schema objects, at this scale, contain a lot of data that has to be memory-accessible to keep latency low. The memory requirements can be too much for most databases. Monolithic databases avoid the problem by keeping the metadata on disk. This makes metadata required for every query and much slower to access. Instead, TiDB leverages an LRU cache and other optimizations to load the object metadata, no matter the size, for use in queries. Busier Forge applications will get better performance because the metadata their queries need will be accessible lightning-quick.

Forge customers will also have differing table sizes and properties that can cause confusion – by the nature of using a single scalable system – in a single global query planner that does cost optimization based on table statistics. This means collecting individual stats from every table of every customer, which then means an enormous amount of statistics. TiDB is designed to intelligently gather these statistics so as to reduce impact on each customer’s traffic.

Conclusion: Scale is an Architecture Problem, Not a Maintenance Problem

Distributed databases like TiDB are the answer to a serious problem that many enterprises are just waking up to. They’re designed with horizontal scale in mind while allowing users to work within the familiar confines of a traditional interface like MySQL. They free developers from the manual, error-prone drudge work of scale: sharding, re-sharding, and rejecting application changes because of data rigidity. When TiDB is in place, organizations that encounter scaling events don’t have to worry about application traffic slowing down or application changes being infeasible. They unlock engineering by removing scaling concerns in the data layer.

If you’re struggling with scale, it’s easy to tell yourself a solution is just around the corner. One more workaround. One more all-nighter. The truth is, any gains you achieve this way won’t last. At least not for long. The reason these problems keep cropping up is you’re struggling with your architecture. You’re trying to make systems do things they were never designed to. Innovating with velocity means building on a foundation designed for scale.

Want to pressure-test your design? Schedule a 30-minute architecture review and get tailored guidance on scale, reliability, and cost.

Webinar

Effective Multi-Tenancy: Scaling SaaS Over 1 Million Tables in a Single Cluster

TiDB Cloud Dedicated

A fully-managed cloud DBaaS for predictable workloads

TiDB Cloud Starter

A fully-managed cloud DBaaS for auto-scaling workloads