Managing memory in a high-performance database environment isn’t just about having enough RAM; it’s about how that RAM is organized. For SREs and DBAs, understanding the nuances of the Linux kernel’s memory management can be the difference between a smooth-running system and unpredictable tail latency.

In this post, we’ll break down the core mechanics of memory fragmentation in Linux. We’ll explore the inner workings of the buddy allocator and its primary defense mechanisms, such as page migration types, while clarifying the critical performance trade-offs between Transparent Huge Pages (THP) and hugetlb. Finally, we’ll walk through concrete diagnostic workflows using /proc/buddyinfo and ftrace to help you quantify how memory compaction impacts tail latency in production environments like TiDB.

Memory Fragmentation, Explained in 60 Seconds

In the context of the Linux kernel, memory fragmentation refers to how physical RAM is allocated and used. It is specifically a concern for RAM and kernel memory, rather than disk defragmentation. The core constraint is contiguous memory allocation: the kernel often requires blocks of memory to be physically adjacent to one another to function efficiently.

When these contiguous blocks are broken up, even if you have gigabytes of “free” memory, the kernel may struggle to find a single block large enough for its needs, leading to performance degradation.

Internal vs. External Memory Fragmentation (Linux Reality Check)

To diagnose performance issues, you must first distinguish between the two types of fragmentation:

- Internal Fragmentation: This occurs when the kernel allocates more memory than is actually requested. The “wasted” space exists inside the allocated block but cannot be used for other purposes.

- External Memory Fragmentation: This is the primary concern for system performance. It happens when free memory is available in the system, but it is scattered in small, non-contiguous “holes”. Consequently, a request for a large contiguous block will fail even if the total free memory is sufficient.

Why Virtual Memory Doesn’t Fully Save You (Kernel + DMA)

You might wonder why fragmentation matters in an era of virtual memory, which maps non-contiguous physical pages into a contiguous virtual address space. While virtual contiguity helps applications, the kernel and hardware have stricter requirements:

- Kernel Linear Mapping: Certain kernel subsystems rely on linear mapping for performance, requiring physical contiguity.

- Device I/O and DMA: Direct Memory Access (DMA) allows hardware devices to move data without involving the CPU. While some modern devices support “scatter-gather DMA,” many older or specialized devices still require large, physically contiguous buffers.

The Buddy Allocator: How Linux Page Orders Create Fragmentation

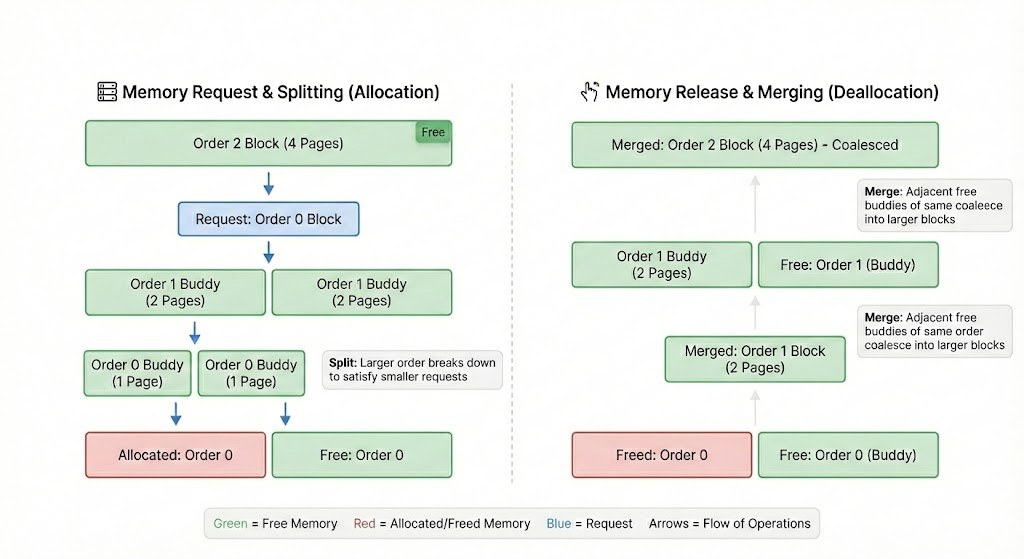

Linux manages physical memory using the buddy allocator. It organizes memory into “orders,” where Order 0 is a single page (usually 4KB), Order 1 is two pages (8KB), and so on, doubling each time.

Figure 1. A Linux buddy allocator showing orders splitting and merging.

When a high-order allocation (a large contiguous block) is requested, the allocator splits larger blocks into “buddies”. Conversely, when blocks are freed, they merge back together. Fragmentation occurs when these high-order blocks become scarce because small, unmovable allocations are scattered across the memory map, preventing buddies from merging.

Where the Slab Allocator Fits (SLUB/SLAB)

While the buddy allocator handles large blocks of pages, the slab allocator (typically SLUB in modern kernels) manages smaller objects like task descriptors or inodes. The slab allocator ultimately consumes pages from the buddy allocator. When slab growth is high, it can place significant pressure on contiguous blocks, contributing to external fragmentation.

Page Migration & Migration Types: Linux’s First Line of Defense

To combat fragmentation, the kernel categorizes memory pages into migration types to prevent “unmovable” pages from polluting blocks that could otherwise be compacted:

- MIGRATE_UNMOVABLE: Pages that cannot be moved, such as those allocated by the kernel.

- MIGRATE_MOVABLE: Pages that can be relocated, typically used for user-space applications.

- MIGRATE_RECLAIMABLE: Pages that can be discarded and freed, like file caches.

When the kernel cannot fulfill a request from the preferred migration type, it performs a “fallback” allocation. Frequent fallback behavior is a clear signal of high external memory fragmentation.

Huge Pages, hugetlb, and Transparent Huge Pages (THP): When Fragmentation Gets Expensive

Distributed SQL databases like TiDB benefit from huge pages, which reduce the overhead of page table lookups. However, because huge pages require large contiguous blocks (e.g., 2MB or 1GB), they make fragmentation much more visible.

| Feature | Transparent Huge Pages (THP) | hugetlb | Explicit Huge Pages |

| Allocation | Automatic by kernel | Pre-allocated at boot/runtime | Manual management |

| Complexity | Low (plug and play) | Medium | High |

| Predictability | Low (can cause latency) | High | High |

| Use Case | General workloads | Databases/Latency-sensitive | Specialized high-perf |

When to Disable THP for Databases (and What to Do Instead)

While Transparent Huge Pages (THP) aim to simplify memory management, it can cause significant latency spikes for databases. The kernel’s background “khugepaged” thread may struggle to find contiguous memory, leading to aggressive compaction and stalls.

For production databases, the standard operational default is to disable THP and use explicit huge pages (hugetlb) instead. This ensures that the memory is reserved at startup, providing predictable performance. For more details, see our guide on Transparent Huge Pages (THP) for databases.

Memory Compaction: How Linux Rebuilds Contiguous Free Blocks

Memory compaction is the process by which the kernel relocates movable pages to create larger contiguous blocks of free space.

While essential, compaction can be a double-edged sword. “Direct compaction” occurs when a process is forced to wait for the kernel to defragment memory during an allocation request, leading to massive latency spikes and performance cliffs.

How to Detect Memory Fragmentation (the Commands that Matter)

Diagnosing fragmentation requires looking beyond basic tools like free or top.

/proc/buddyinfo: Shows the count of available blocks for each order across different memory zones. If the numbers are high for Order 0 but low for Order 10, your system is heavily fragmented./proc/pagetypeinfo: Provides insight into the distribution of migration types and how often fallbacks are occurring.- Fragmentation Index: Some kernels provide a fragmentation index via /sys to quantify the severity of the issue.

Measure External Fragmentation Events with ftrace (Step-by-Step)

For a deep dive, you can use ftrace to capture fragmentation events in real-time:

- Enable the event:

echo 1 > /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem/mm_page_alloc_extfrag/enable - Collect data:

cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe > frag_log.txt - Interpret results: Look for “fallback” events. An example event line might look like this:

mm_page_alloc_extfrag: page=0x12345 pfn=74565 alloc_order=9 fallback_order=0 - Parse with awk:

awk '/fallback_order/ {print $NF}' frag_log.txt | sort | uniq -c - Disable tracing:

echo 0 > /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/events/kmem/mm_page_alloc_extfrag/enable

Mitigation Checklist for Production Database Servers

To maintain a healthy Linux environment for your databases, follow this checklist:

- [ ] Reduce high-order dependencies: Avoid kernel-level configurations that require massive contiguous blocks at runtime.

- [ ] Set a Huge Page Strategy: Choose between THP and hugetlb intentionally; for databases, explicit huge pages are usually preferred.

- [ ] Baseline Performance: Establish a baseline for compaction and fallback events so you can alert on sudden spikes.

- [ ] Trace System Behavior: Use tools like ftrace to trace Linux system behavior in production with minimal impact.

Why this Matters for TiDB Workloads (Predictable Tail Latency)

In distributed databases like TiDB, consistent performance is key to meeting Service Level Objectives (SLOs). When memory fragmentation triggers background compaction or direct reclaim, it directly translates into database tail latency. By understanding and mitigating these kernel-level bottlenecks, you ensure that your deployment options for predictable performance remain stable even under heavy load.

Ready to see how TiDB handles high-performance workloads? Modernize MySQL workloads without manual sharding or explore Linux kernel memory fragmentation, continued (Part II) for even deeper technical insights.

FAQ: Memory Fragmentation in Linux (Quick Answers)

Can RAM be Fragmented?

Yes. While RAM doesn’t have moving parts like a hard drive, “fragmentation” refers to the lack of contiguous physical memory blocks, which the Linux kernel requires for certain operations.

Is Fragmentation Still an Issue on Modern Kernels?

Absolutely. While modern kernels have improved compaction algorithms and migration types, the increasing use of huge pages and massive RAM capacities makes the impact of fragmentation even more significant.

Does Compaction Always Help?

Not necessarily. While it frees up contiguous blocks, the CPU overhead of moving pages can cause performance degradation that outweighs the benefits, especially during “direct compaction”.

Experience modern data infrastructure firsthand.

TiDB Cloud Dedicated

A fully-managed cloud DBaaS for predictable workloads

TiDB Cloud Starter

A fully-managed cloud DBaaS for auto-scaling workloads